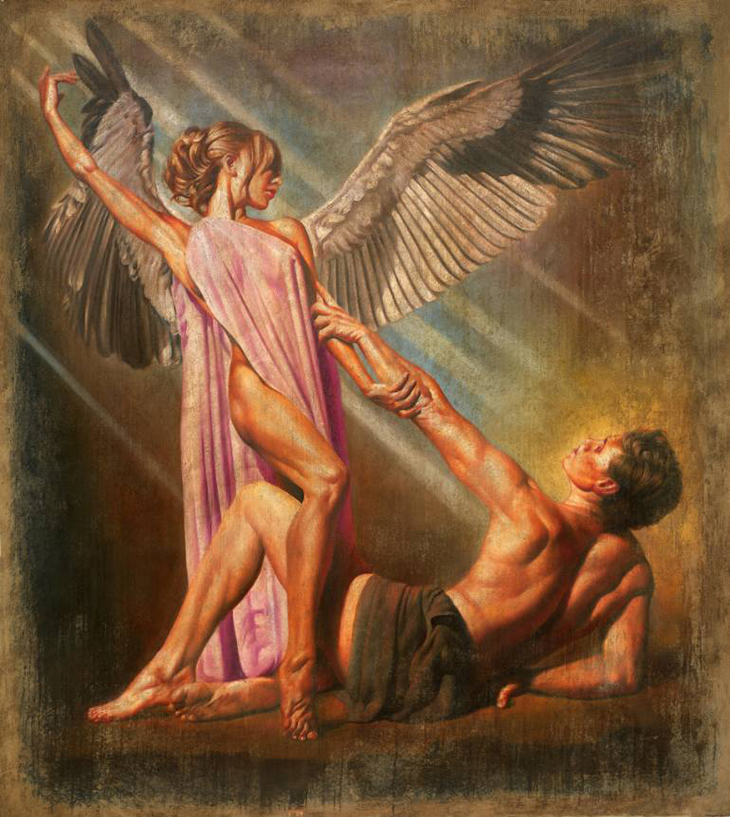

In modern times, spirituality and eroticism seem to be two separate and mutually exclusive concepts. In this article I will focus on ancient Greece and their view of spirituality and eroticism.

Plotinus (204/5 – 270 C.E.), is generally regarded as the founder of Neoplatonism. He is one of the most influential philosophers in antiquity after Plato and Aristotle. The term ‘Neoplatonism’ is an invention of early 19th century European scholarship and indicates the penchant of historians for dividing ‘periods’ in history. In this case, the term was intended to indicate that Plotinus initiated a new phase in the development of the Platonic tradition.

It has often been noted that Plotinus’ use of erotic imagery diverges in significant ways from that of Plato. The notion of eros as the impetus for philosophical ascent already occurs prominently in the Symposium, where the process is said to begin with sexual desire for beautiful male bodies; this attraction is gradually sublimated into desire for progressively more abstract notions of beauty, until the final stage at which sexual love must be superceded for the soul to be able to contemplate Beauty itself.

For Plotinus, by contrast, the soul’s unbounded love for the One persists and even attains florescence at the ineffable moment of mystical union. Moreover, Plotinus extends the erotic imagery in ways that would have been unthinkable to Plato, not only by describing the initial stages of ascent with remarkably explicit (but often under-translated) erotic language, but more importantly, by comparing the experience of mystical union with the One to an act of sexual intercourse. In treatise VI.9 – thus already in his very first account of the ultimate union – he describes it in graphically sexual terms; in chapter 4 he says it is ‘a kind of erotic experience like that of a (male) lover resting in the (male) beloved’, while later, in chapter 9, he contrasts love for the One with worldly love, but still describes the former with strikingly sexual language: ‘But there is our true love, with whom also we can be united, having a part in him and truly possessing him, not embracing him in the flesh from the outside’; he then insists that we should ‘embrace him with the whole of ourselves and have no part with which we do not touch God’.

Similarly, in treatise VI.7, the images range from the relatively simple analogy between those who behold the One and lovers who have sex with their beloved (chapter 31), to the rather more concrete statement that the desire of lovers to be blended together (sugkrinai) with each other sexually is in fact an ‘imitation’ (mimêsis) of the soul’s mystical union with the One (chapter 34).This sort of imagery seems to go well beyond the sublimated or metaphorical eroticism one finds in Plato.

In chronological terms, these Plotinian passages are perhaps the first fully explicit examples of a long literary tradition of erotic mysticism, a tradition whose tropes are now familiar to us from their medieval Christian, Jewish, and Islamic formulations. In traditional theological exegeses, the erotic imagery of the mystics has typically been interpreted as a commonplace metaphor (if not a cliché) for intense but essentially chaste religious devotion, whatever it was that the mystics themselves had actually experienced. Yet much recent scholarship on medieval mysticism has called into question precisely the assumption that the sexual language used by mystics was intended to describe an entirely non-somatic, ‘spiritual’ experience. Indeed, there may instead be good reason to suspect that many of these mystics’ erotic experiences of the Divine cannot be clearly distinguished from the affective and even physiological aspects of embodied sexuality. How, then, are we to understand Plotinus’ erotic mysticism? Is this imagery of sexual love just (as many modern interpreters seem to imply) a striking metaphor for an emotionally intense (but in fact sterile and desexualized) love of the Good?

Sexual love and its relationship with love of the One

Here I would like to question the common assumption that Plotinus’ use of sexual imagery to describe mystical union is unproblematically ‘metaphorical’, (whatever this might mean). In order to understand what Plotinus intends to express with this comparison, we must first understand that to which he is comparing the mystical union; and this requires that we examine his complex notion of sexual love. It is significant that according to Plotinus’ explicit theory of eros, human sexual love is intimately related to, and in fact dependent upon, the soul’s mystical desire for the One, since all forms of love – that of the soul in its individual, cosmic, and hypostatic modalities, that of Intellect, and even that of the One itself – are ultimately expressions of desire for the One. Plotinus’ most explicit discussion of the specifically psychic aspect of love, which includes human sexual attraction, runs throughout his ostensible exegesis of Plato’s Symposium in treatise III.5, ‘On Love’.

In the first chapter, Plotinus generally follows Plato in his claim that the passion of human sexual love is the desire or longing (orexis) for beauty and thus ultimately for the Good (or the One). His essential argument is that what we perceive as human beauty is actually a reflection of the Form of intelligible Beauty upon the corporeal substrate, and further, that this intelligible Beauty originally derives from the One. The necessary conclusion is that sexual love is always, ultimately, a desire for the One, whether or not we are conscious of its true object. In the subsequent chapters of the treatise, Plotinus explains the origin of love with a tendentious interpretation of Diotima’s allegorical myth of Eros and Aphrodite (Symposium 203b–204a).

According to Plotinus, Eros is not only a psychic passion but also an independent entity arising from the hypostatic Soul’s initial glimpse of the beauty of Intellect. More specifically, Eros emerges simultaneously as an efflux of the ‘eye’ of the Soul and also as the power of the vision of Intellect itself; it thus mediates between lover (the Soul) and beloved (the Intellect). Lesser Erôtes are similarly born from the desire of subordinate types of soul as each glimpses a correspondingly dimmer reflection of beauty. This results in a hierarchy of interrelated psychic loves, each correlated with the type of soul on its respective ontological level, and each in turn inspiring a passion for the ultimate source of this beauty, which is, in each case, the One.

This dynamic is evident throughout Plotinus’ system; thus, at the level of Nous, love similarly arises from a primordial vision, although in this case the vision is directly of the One. At VI.7.35, 20–6, Plotinus distinguishes between two states of Intellect: the normal state, in which it thinks rationally, and the other, exceptional state, that of the ‘Intellect in love’ (nous erôn), whose intoxicating glimpse of the One has rendered it insane. This latter state is necessary for Intellect to transcend its own cognitive limitations and attain the final, hyper-noetic union.

Here Plotinus explicitly equates this love with the immediate, non-discursive self-perception of the One by which the emergent Intellect first acquired definition and independent subsistence. Intellect’s erotic attraction results in its epistrophê towards the One, and attains its (seemingly orgasmic) fulfilment in mystical union. This is possible, however, only because of the One’s own abundantly erotic nature, the latter being ‘loveable, and love, and love of himself’. The One also contributes to the love that arises in each subsequent hypostasis, giving a ‘trace of itself’ (ichnos autou) to its subordinates and eventually squirting a kind of ‘grace’ (charis) into the soul. This erotic efflux in return kindles the soul’s desire for its source.

For Plotinus, then, every form of love is correlated with epistrophê and instils a desire, conscious or unconscious, for union (or rather, reunion) with the One. Yet at this point one could still suppose that Plotinus saw a substantial distinction between metaphysical and worldly love. In certain places he seems to suggest that actual sexual intercourse is a kind of failure (although I differ from the majority of scholars in seeing his position on sexual love as deeply ambiguous and at times surprisingly positive). In any case, one might imagine that in Plotinus’ view it is only at the lower end of this spectrum that love becomes ‘sexual’, strictly speaking; in other words, that it involves physical bodies, sexual fluids, biological reproduction, and so forth.

Plotinus seems to be suggesting as much at VI.9.9: first, with his interpretation of the Platonic division of Aphrodite into two distinct but related manifestations, one ‘heavenly’, representing the soul’s love of God in the intelligible world, the other whorish and ‘vulgar’ (pandêmos), presiding over terrestrial sexual love (lines 29–33); and second, with his comparison between the soul’s love for the One and that of a girl for her father (Freudian interpretations notwithstanding), and the subsequent contrast between this ‘noble’ love and other more mundane loves (lines 33–44). Nevertheless, he emphasizes the interrelation and even consubstantiality of all forms of love, both in this passage and in an extended passage at III.5.4, in which he says that all subordinate ‘Aphrodites’ flow from, and depend upon, a universal Aphrodite. Human sexual love and the Soul-as-Intellect’s love for the One are therefore consubstantial as well as functionally analogous; and if they do occupy different ontological strata, they are still intimately related, as opposite poles of a unified continuum.

- This article is a short excerpt from the book: Late Antique Epistemology: Other Ways to Truth